Clinical

Glaucoma: A clear role for pharmacy

In Clinical

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Recent studies suggest that community pharmacists should be part of glaucoma management pathways

Key facts

• Increased intraocular pressure is the main risk factor for glaucoma

• The risk of glaucoma rises by 73 per cent for each decade increase in age after 40 years

• Chronic open-angle glaucoma is the most prevalent form

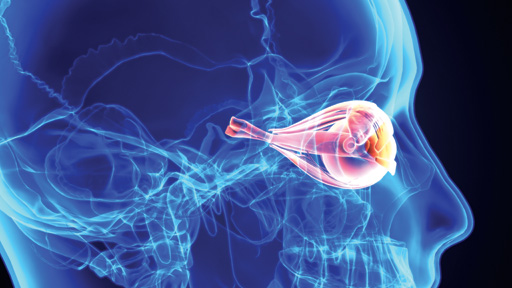

Glaucoma threatens a precious and truly remarkable sense. The International Glaucoma Association (IGA) estimates that it is responsible for about one in 10 of the 360,000 people who are registered as blind in the UK.1 Historically, community pharmacists have not routinely been part of the structured strategies to manage glaucoma – but recent studies have suggested that they should in fact be part of glaucoma management pathways.1,2

Under pressure

Aqueous humour supplies oxygen and nutrients to the cornea and lens, and helps maintain the eye’s shape. The ciliary body produces aqueous humour, which flows into the anterior chamber through the pupil. Most aqueous humour drains through the trabecular meshwork into the canal of Schlemm. Some drains through the iris root (known as uveoscleral outflow).3

Several factors increase the risk of glaucoma including:

• Ethnic background – people of African ethnicity seem to be almost three times more likely to develop glaucoma than white Europeans

• Other members of the family with glaucoma

• Diabetes

• Advancing age.4,5

Increased intraocular pressure (IOP) is, however, the main risk factor. Each additional mmHg rise in IOP increases the risk that glaucoma will progress by 11 per cent.3

The increased IOP damages the retina. Nerves from the light-sensitive rods and cones in the retina feed into ganglion cells, which, in turn, give rise to axons. These merge into the one million axons that form the optic nerve, which leaves the eye through the optic disc at the back.6 A depression at the centre of optic disc – the cup – is normally relatively small. In people with glaucoma, however, increased IOP destroys retinal ganglion cells, thins the layer of retinal nerves and enlarges optic disc cupping.4

Nevertheless, some people with raised IOP do not develop glaucoma (a condition called ocular hypertension) and about half of glaucoma patients have IOP in the normal range (10-21mmHg) at diagnosis (normal tension glaucoma).3,5 Variations in the susceptibility of the nerves to damage from pressure seem to account for these differences.4

Chronic open-angle glaucoma, which affects about 480,000 people in England,1 is about seven times more common than the next most prevalent form, chronic angle-closure glaucoma.5 In open-angle glaucoma, changes to the outflow pathway, such as blockage of the meshwork with debris and age-related changes to cells and repair mechanisms, cause the rise in IOP. The risk of glaucoma rises by 73 per cent for each decade increase in age after a person reaches 40 years.4 In angle-closure glaucoma, the iris blocks the anterior chamber angle, which means the aqueous humour cannot drain away.5

Untreated, both forms of glaucoma cause progressive, irreversible visual field loss. This may progress to tunnel vision and, ultimately, loss of central vision.5 However, defects in visual field emerge only after the patient has lost about 30 per cent of their retinal ganglion cells,5 which underscores the importance of early screening.

Poor adherence

According to NICE, with effective treatment most people with glaucoma don’t go blind and have a good quality of life.7 Lowering IOP by 30-50 per cent from baseline usually halts the progression of glaucoma4 but non-adherence rates are between 5 and 80 per cent. Poor compliance may account for approximately 10 per cent of visual field defects.8

In a study of 131 glaucoma patients who had used eye drops for six months, 45 per cent reported some degree of non-adherence.9 Another study, which enrolled 123 patients with primary openangle glaucoma, found that forgetfulness emerged as the commonest reason for non-adherence (reported by 43.8 per cent of patients).8

Meaningful contribution

Against this background, a study by the London North West Local Pharmacy Forum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society and the IGA showed that community pharmacists can “contribute meaningfully to the management of glaucoma patients”.2

During the study, 18 community pharmacists approached glaucoma patients opportunistically when they collected medication. The pharmacist provided patients with individualised support and advice.2

An initial consultation was attended by 110 patients (mean duration 15 minutes) and 95 attended the follow-up consultation (mean duration 10 minutes), typically four to eight weeks later. During the initial consultation, pharmacists counselled 90 per cent of patients about some aspects of their use of eye drops and 93 per cent received printed information addressing topics about which they had been unaware.2

Numerous outcomes improved between the initial and follow-up consultations. For example, the proportion of patients who received instruction about eye drop use rose from 53 to 84 per cent, while those with sufficient understanding of glaucoma and medication increased from 57 to 97 per cent.

Awareness about UK driving regulations increased from 47 to 75 per cent. All these differences were statistically significant. Moreover, 95 per cent of patients said that the pharmacist consultations had been helpful.

“Utilising community pharmacy expertise in future glaucoma management pathways should be considered,” the authors concluded.2

Further evidence

Powys Teaching Health Board and the IGA developed an audit toolkit for pharmacy staff, which was evaluated in 23 pharmacies for one month or until 30 patients (or their carers) were interviewed. Pharmacy staff could access educational resources, such as a video on eye drop administration.1

Of the 238 patients who participated, 57 and 33 per cent showed good and moderate eye drop technique respectively. The proportion of patients assessed as having “good” technique varied between pharmacies from 10 to 100 per cent. The variation may reflect the subjective nature of the assessment or differences in the advice and support patients previously received. Nevertheless, 43 per cent of patients seemed to administer eye drops incorrectly.1

Twenty-one per cent experienced difficulty self-administering eye drops and would probably benefit from a compliance aid to support positioning, squeezing the bottle, or both. Of these 47 patients, 13 bought or were prescribed at least one compliance aid such as Opticare, Opticare Arthro, Autodrop and Autosqueeze.1

Many people need more than one drug to adequately lower IOP. The IGA advises that patients should wait at least five minutes between eye drop applications. Of the 194 patients prescribed more than one preparation for glaucoma, 11 per cent waited less than five minutes and 22 per cent “no significant time”. Again, the study uncovered considerable variation. Three pharmacies reported that all patients waited for at least five minutes, while another reported that 80 per cent left no significant gap.1

Thirty-two per cent of patients had received a MUR within the current year. Of the other 57 patients who were offered a MUR, 66 per cent agreed to participate. The study also found that about 20 per cent of patients received insufficient quantities of medication to facilitate good adherence, while six per cent stored their eye drops inappropriately.1

95 per cent of patients said that the pharmacist consultations had been helpful

Central role

These studies suggest that pharmacists can contribute to glaucoma management. For example, pharmacists can check for comorbidities or potential drug interactions.7 They should also stress the importance of adherence.7

“It is absolutely vital that medication for conditions like glaucoma is used promptly and regularly to ensure people retain their sight,” Helen Lee, policy and campaigns manager from the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) told Pharmacy Magazine. “Pharmacists play an instrumental role in supporting patients to adhere to their treatment regimen. By helping patients to understand possible side-effects and repercussions of nonadherence, pharmacists can help ensure that they are aware of the risks of missing doses. Pharmacists can also share strategies to sustain a treatment routine that fits in with a patient’s daily life and advise on how to adapt that routine when it could be disrupted, such as when a patient goes on holiday.”

In addition, NICE says that people with glaucoma need to be aware of the importance of regular monitoring, support organisations and patient support groups, and driving regulations.7

“Pharmacists must ensure that patients are able to read the packaging and instructions that come with their treatment by adhering to the Accessible Information Standard,” Helen Lee adds. “For example, patients who read braille should be able to read the medication names on packaging without labels being placed over the top, and patients who need large print or any other alternative format should be given appropriate communications so they can read instructions or medication labels easily. This guarantees that patients can manage their eye health properly and independently.”

Further information

• Royal National Institute of Blind People: rnib.org.uk; helpline: 0303 123 9999

• International Glaucoma Association: glaucoma-association.com; sightline: 01233 648170