Surface tension: Latest developments in skin care

In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Common dermatological diseases are an area where community pharmacists and their teams can help to guide and support patients to good effect

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you should be able to:

- Describe the most common skin conditions and how they can be treated

- Understand the latest thinking regarding therapeutic developments in dermatology

- Ensure patients with skin conditions get the best advice and quality of care from pharmacy

With so many patients with skin problems preferring to treat themselves rather than seek medical advice, it is up to pharmacy teams to ensure they are doing it right. Acne and the inflammatory skin diseases are long-term conditions for which patients may require ongoing support over a period of years. Let us consider the most common skin conditions and their treatment.

Key facts

- Propionibacterium acnes has been renamed Cutibacterium acnes following genomic investigations

- Many dermatologists now recommend maintenance treatment for eczemaprone areas of the body

- Several new biologics have recently been approved for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis

Acne

Acne treatments are often not 100 per cent effective. Antibiotic resistance (especially to erythromycin and clindamycin) is common in Propionibacterium acnes and patients are often prescribed treatment with no follow-up to assess response and receive little supporting advice. Patients often struggle to use prescribed and OTC treatments effectively and can be unaware of how to care for their skin to best effect during treatment.

Acne commonly affects teenagers, although it can continue for many years, and has a profound impact on self-confidence and self-esteem. Lack of awareness about treatment can be a major hurdle. “One of the most useful things we can do is to let young people know there are treatments available that can make most of them acne-free,” says Katherine London, consultant dermatologist, St Luke’s Hospital, Bradford.

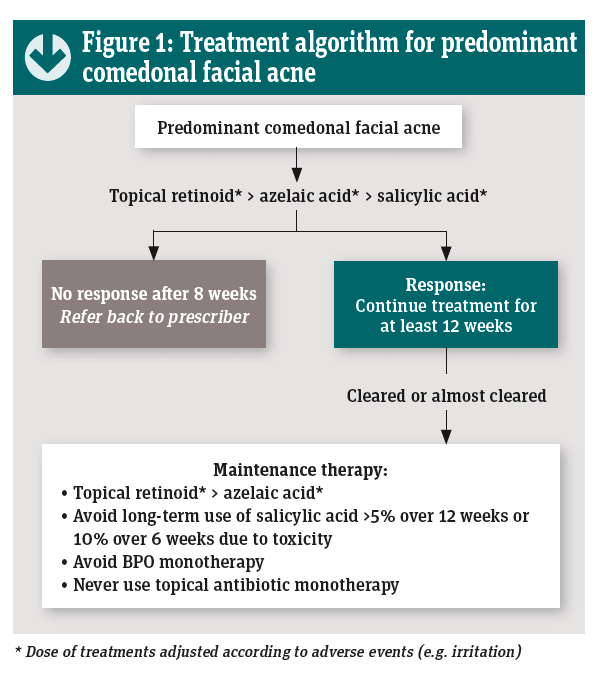

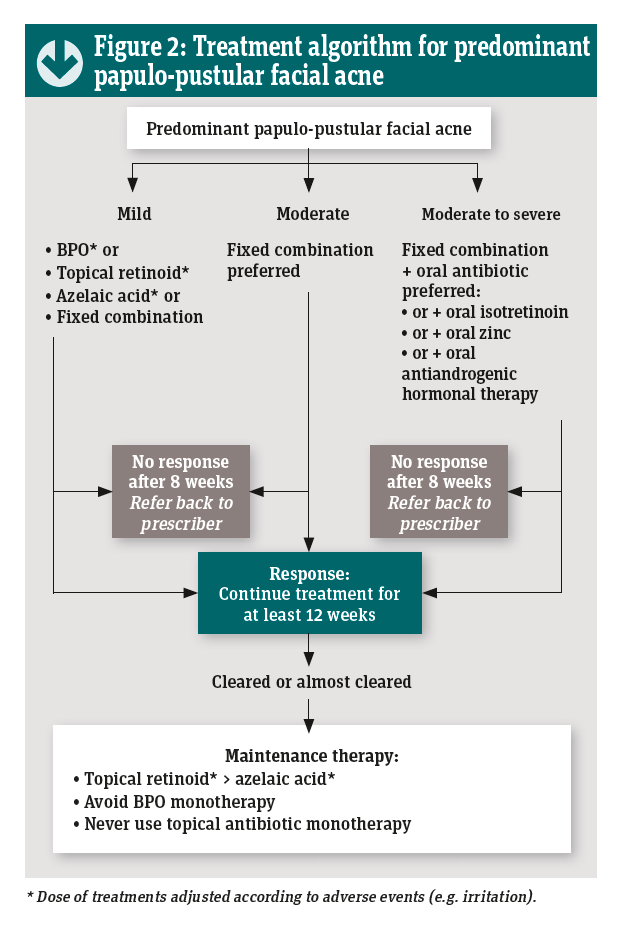

A consensus guide to acne treatment, based on evidence-based guidelines, provides ‘clinician-friendly’ algorithms and checklists for day-to-day acne management (see Figures 1 and 2).1

What’s new in acne?

Propionibacterium acnes has been renamed Cutibacterium acnes following genomic investigations. Propionibacteria are widely distributed in nature but only a small number of these have adapted to live on human skin in contrast to other members of the genus that live in diverse habitats (e.g. cows’ stomachs and Swiss cheese). It is those that live on human skin that have been renamed.

C. acnes is part of the normal human skin flora (and is important for skin health) and was believed to colonise pilosebaceous follicles and proliferate when sebum secretion was increased and hypercornification of follicles occurred at puberty.

“Why C. acnes should cause acne in some individuals but be a harmless bystander in others was not clear,” said Professor Lajos Kemény of the University of Szeged, Hungary, speaking at the European Association for Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress in Budva, Montenegro in May. Recent findings show that people with acne do not have more C. acnes in their pilosebaceous follicles than normal individuals.

Genomic investigations have identified numerous different strains of C. acnes – some are found exclusively on skin with acne and some exclusively on healthy skin.”You can think of them as good, neutral and bad strains of C. acnes,” said Professor Lajos. It has also been shown that C. acnes is able to form biofilms that hinder penetration of antibiotics.

Current thinking suggests that acne is not the result of proliferation of C. acnes but of a selection of a subset of pathogenic C. acnes strains that behave differently (more virulent, more inflammatory, more inclined to form biofilms). This is presumed to trigger innate immune responses leading to inflammation. This new understanding could open other avenues for treatment (e.g. biofilm disruptors such as myrtacine and/or probiotics to restore a healthy skin microbiome).

What can you do?

- Reinforce the importance of eight weeks’ treatment, then assessment of response

- Note that topical adapalene (a compound that has retinoid-like activity) can be safely used by young women. In the US it has been available OTC for a couple of years

- Ensure that patients understand how to care for their skin during treatment and have:

o A mild wash product to cleanse skin (e.g. Cetaphil Gentle Skin Cleanser, Eucerin Dermopurifyer Cleansing Gel)

o An oil-free (non-comedogenic) moisturiser (e.g. Eucerin Dermopurifyer Adjunctive Soothing Cream, Cetaphil Moisturising Cream)

o A sunscreen – ideally a non-comedogenic product such as Eucerin Oil Control Sun Gel Cream.

• Advise patients that maintenance therapy is recommended because acne is a long-term condition. The preferred maintenance treatment is a topical retinoid (although low-dose oral isotretinoin is prescribed off-label by some dermatologists and there is mounting evidence for its effectiveness.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that follows a relapsing and remitting course. Chronic plaque psoriasis is the commonest form and this typically presents as well-defined, raised, red plaques covered with whitish scales on the elbows, shins and back. It can also affect the scalp and skin folds. Nails are often affected and up to 30 per cent of people with psoriasis also have associated joint disease.

The cause is not known but activated T-cells are known to play a central role. Psoriasis is also associated with co-morbidities including cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome. In addition, it can have a profound impact on quality of life. The majority of patients have mild or moderate disease that responds to topical treatment but about 20 per cent have severe disease that requires systemic treatment.

Most patients will have a topical treatment for the trunk and limbs, often starting with a combination product (calcipotriol and betamethasone). The Primary Care Dermatology Society provides clear recommendations on the management of psoriasis (see pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/psoriasis-an-overview).

What’s new in psoriasis?

Apremilast is one of the most exciting recent developments in the management of this disease because it is an oral treatment. Apremilast (Otezla from Celgene) is a small-molecule, phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitor, which down-regulates the inflammatory response by reducing the amounts of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)€‘alpha and interleukin (IL)€‘23 in the skin.

Apremilast is recommended as an option for treating moderatesevere chronic plaque psoriasis in adults whose disease has not responded to other systemic therapies, including ciclosporin, methotrexate and PUVA (psoralen and ultraviolet€‘A light), or when these treatments are contraindicated or not tolerated.

“Apremilast is particularly useful for patients with cancer [who cannot be given ciclosporin or methotrexate] and for managing hard-to-treat areas,” says Professor Shernaz Walton, consultant dermatologist, Hull and East Yorkshire NHS Trust.

In trials, apremilast was less effective but also less costly than biological therapies.2 Apremilast is also effective in psoriatic arthritis and treatment is associated with weight loss and nail improvements.

Biologics often provide long-lasting relief from psoriasis symptoms and several new biologics have recently been approved for treatment of moderate-severe psoriasis. In addition to the existing biologics – adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab (anti- TNFs), ustekinumab (IL-12/23 inhibitor) – there are now also secukinumab, ixekizumab and brodalumab (IL-17A inhibitors) and guselkumab (IL-23 inhibitor). Several more biologics are currently undergoing review by NICE.

Finally, the development of a foam formulation of Enstilar, the calcipotriol and betamethasone combination, offers improved delivery of the drugs in a formulation that is pleasant and convenient to apply.

What can you do?

- Reinforce advice on discontinuing treatment with calcipotriolbetamethasone combination when the plaques go flat (although they may still be reddish) to avoid unnecessary long-term exposure to the topical corticosteroid

- Encourage regular use of a humectant-containing emollient to keep the skin soft and pliable and to minimise shedding of skin scales

- Check that patients also have treatments for four key areas – trunk and limbs, face, flexures and genitals, and scalp – and know which is which and how to apply them

- Enquire about joint disease – early treatment of psoriatic arthropathy is associated with better long-term outcomes

- Enquire about cardiovascular risk factors and offer healthy living advice and/or signposting for screening

- Signpost patients to the Psoriasis Association (psoriasisassociation. org.uk) and/or the Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthropathy Alliance (papaa.org) for ongoing support and information.

Eczema

Eczema is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that typically presents as areas of red, itchy, inflamed skin, often affecting the skin creases where the skin is thinner. It is characterised by intermittent flare-ups separated by periods of remission.

The condition affects about 20 per cent of children under the age of five years and up to 10 per cent of adults. Many children have mild-moderate eczema that can be treated topically but a few have severe disease that requires systemic treatment.

Eczema can have a serious impact on quality of life for the child affected and the whole family. In addition, “there is a growing understanding that the chronic inflammation directly affects brain function, starting with mild symptoms such as separation anxiety and eventually progressing to depression, substance misuse and even suicide”, says Professor Mike Cork, consultant dermatologist, Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust.

Treatment of eczema is based on assiduous use of emollients to restore and maintain the skin barrier, together with prompt use of topical corticosteroids and/or topical calcineurin inhibitors to control flare-ups.

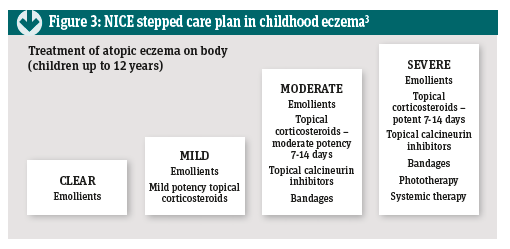

Humectant-containing emollients have a longer-lasting effect than simple emollients and should always be suggested. The NICE guideline on childhood eczema recommends a stepped care approach in which the treatment is matched to the severity of the disease and stepped up or down according to response (see Figure 3).3

Many dermatologists now recommend maintenance treatment for eczema-prone areas of the body, rather than waiting for the next flare-up and then treating accordingly. One approach is to use a topical calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus) on two, nonconsecutive days of the week.

The other approach is to use so-called ‘weekend treatment’ with potent topical corticosteroids. In this case, the treatment is applied on two consecutive days of the week. Studies have shown that this is effective in prolonging periods of remission in both adults and children.

What’s new in atopic eczema/dermatitis?

Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks IL-4 and IL-13, a fundamental step in the inflammatory process in eczema. The drug, which is administered by subcutaneous injection, “brings patients back to normal life”, according to Professor Diamant Thaçi from the University of Lübeck. Dupilumab treatment dramatically improves skin condition and reduces itching. “It is not immunosuppressive and we do not see an increase in infections,” he adds. A Technology Appraisal guideline is expected from NICE soon.

Crisaborole is a small-molecule PDE4 inhibitor that is used topically as a 2% ointment. PDE4 inhibition interferes with the inflammatory process by reducing levels of TNF-alpha and cytokine mediators. The drug has proved to be effective for healing eczematous skin and reducing itching. It has been launched in the US but is not yet available in Europe.

What can you do?

- Reinforce the importance of regular use of emollients together with topical corticosteroids when eczema is flaring and alone when it is not

- Help patients to find emollients that suit their needs and preferences, ensuring that they have the opportunity to try a humectant-containing emollient

- Explain the stepped-care approach – noting that stepping down when the flare is under control minimises the risk of skin-thinning due to overuse of topical steroids

- Ensure that patients have sufficient quantities of treatments and are able to recognise a flare-up and start treatment promptly as this can reduce both duration and intensity

- Explain how maintenance therapy works by prolonging periods of remission

- Signpost patients to the National Eczema Society for ongoing support and information.

“How dupilumab changed my life”

At the recent BAD annual meeting in Edinburgh, one patient with a lifelong history of severe eczema told how she had contacted Dignitas to arrange assisted suicide but was refused because she was judged to be mentally ill. Jane talked with Professor Mike Cork from the University of Sheffield, describing how eczema had affected her life and the transformation brought about by treatment with dupilumab. (The patient’s name has been changed to protect her privacy.)

Jane’s eczema started at 18 months. By the age of four she required hospital in-patient treatment. She recalled being called “scabby” at school and that “the disease was isolating because I was allergic to so many things”. She missed a lot of education and subsequently found it difficult to work because of frequent flare-ups, lack of sleep and constant pain.

Although Jane married twice she was unable to have children because of premature ovarian failure. “By then I was on a rollercoaster of depression, sleep-deprivation, flare-ups and anxiety,” she said. Jane was eventually diagnosed with steroid-induced bipolar disorder and adrenal insufficiency as a result of long-term steroid treatment. I lost my job, my home, my relationships and my independence – I had lost control of my body and my mind,” she said.

No-one seemed to know how to treat her and her thoughts turned to suicide. However, when she contacted Dignitas, her request was declined because of her mental illness. “Chronic inflammatory disease affects neurotransmitters in the brain leading to suppression of serotonin and melatonin, resulting in depression, anxiety and sleep deprivation,” Professor Cork explained. “Every year a few people with eczema are driven to suicide by their disease,” he added.

Jane eventually received dupilumab on compassionate grounds. Within two weeks the itching decreased markedly, sleep improved dramatically and her skin started to heal. Today her life has changed completely and she has become a successful, out-going individual who is enjoying life to the full.

Professor Cork and Jane agreed on the need for greater awareness of the psychological impact of eczema and the importance of effective treatment. She also made a plea for better monitoring of side-effects. “I got adrenal insufficiency; this would not have happened if I had been properly monitored,” she said. In future, early treatment with dupilumab could avoid much of the suffering experienced by people with severe eczema, Professor Cork concluded.

Rosacea

Rosacea is commoner than is often realised, affecting up to 10 per cent of the population and causing considerable embarrassment and psychological distress for some. It is defined as persistent facial redness, often accompanied by pustules and papules, and often with very sensitive skin. There can also be associated ocular symptoms (e.g. blepharitis and ‘gritty eyes’) and rhinophyma (thickening and enlargement of the skin on the nose).

Redness worsens in response to triggers that can include spicy food, a hot environment, alcohol and stress. The cause of rosacea is unknown but it is now recognised as an inflammatory skin condition with a neuro-vascular component. Demodex mites (present on all facial skin) could also play a role. Until recently, dermatologists classified rosacea into four sub-types but these did not guide treatment satisfactorily because many patients had overlapping symptoms.

What’s new in rosacea?

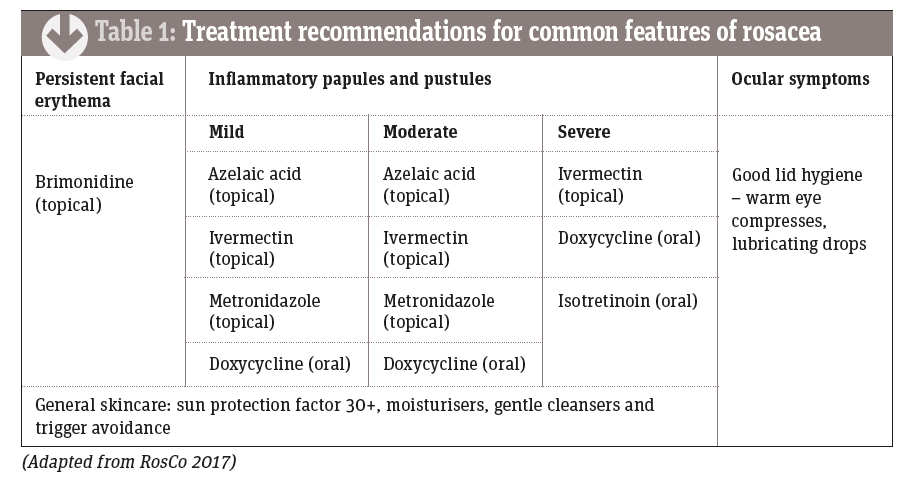

The Rosacea Consensus (RosCo) recommendations adopt a ‘phenotype-led’ approach in which a combination of treatments is used according to the individual pattern of symptoms – together with a battery of general skincare measures.4 These are summarised in Table 1.

Brimonidine gel causes rapid vasoconstriction, reducing flushing for up to 12 hours. An alpha-adrenergic receptor agonist, brimonidine has been used in eye drops to treat glaucoma for many years. It can make pustules appear more pronounced once the background erythema is reduced. The redness returns once the drug effects wear off.

Azelaic acid has a mild effect in rosacea and can sting on initial application.

Ivermectin 1% cream is applied once daily to treat papulopustular rosacea. It was superior to metronidazole 0.75% in one large study.5

Oral doxycycline 40mg modified release (MR) is thought to act mainly as an anti-inflammatory agent as, at this dosage, it has no antibiotic affect. The 100mg dose has the same effect and is cheaper but also affects microbial resistance and the microbiome.

What can you do?

- Reinforce the importance of eight weeks’ treatment, then assessment of response

- Reinforce trigger identification and avoidance where possible

- Ensure that patients have a mild wash product to cleanse skin, an oil-free (non-comedogenic) moisturiser and a sunscreen SPF 30+

- Suggest green-tinted moisturisers or foundation products to counteract persistent redness (e.g Eucerin AntiREDNESS Concealing Day Cream SPF 25 + UVA, Clinique Redness solutions, Avene Antirougeurs)

- Advise patients that maintenance therapy is recommended because rosacea is a long-term condition. Current recommendations suggest continuing to use the minimum treatment to achieve satisfactory control

- Note that although older text books called this condition ‘acne rosacea’, it is not a form of acne.

Latest thinking in dermatology

Dr Christine Clark reports from the British Association of Dermatologists annual meeting, which was held earlier this year in Edinburgh

IBD and skin cancer risk

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are receiving immunosuppressive drugs (such as azathioprine or anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies) are at increased risk of developing skin cancers and may not receive sufficient advice about how to minimise their risks, according to recent research.

Dr Catriona Gallagher and colleagues at Tallaght Hospital, Dublin, have developed an animated cartoon video to educate these patients. The video emphasises the practical steps patients should take, such as using SPF 50 sunscreen every day on exposed skin and wearing a hat that shades the neck and ears. It also describes the appearance of skin cancers in everyday terms. When the impact of the video on IBD patients was evaluated, Dr Gallagher noted that 36 per cent of the group routinely used sunbeds (a known risk factor for skin cancer) – a finding she described as “quite shocking”.

Epidemic of acrylate allergy

“The UK is facing an epidemic of acrylate and methacrylate allergy and awareness of this needs to be raised to protect consumers,” Dr Ian Coulson told the audience. Acrylates and methacrylate are potent sensitisers that are widely used in acrylic, sculptured, gel and shellac nails and in nail glue.

When a gel nail polish is applied, the nails are held under an ultraviolet light source to polymerise the acrylate. Acrylate monomers are the sensitisers and the polymers are usually non-allergenic. Allergy sufferers develop contact dermatitis affecting the hands, feet or face. Acrylate allergy is commonly seen in young women, especially nail technicians. People can be exposed to acrylates through nail products, eyelash glue, dental products and surgical glues. Nitrile gloves provide temporary protection.

“Consumers may not know the risks of sensitisation,” said Dr Coulson. Once sensitised, allergic contact dermatitis may be triggered by acrylates from other sources, including some paints or printing materials, he explained.

Optimisation of psoriasis treatment Emerging data have thrown light on effective ways to use the available treatments for severe psoriasis, according to Professor Richard Warren from the University of Manchester. Key points include:

- Subcutaneous methotrexate may provide a more durable response than oral treatment

- Neither infliximab nor etanercept should be used routinely now that more effective agents are available

- Anti-drug antibodies (ADA) develop rapidly with adalimumab; drug levels of more than 4.6mm/L are not associated with any further increase in response, so there is no need to increase doses to get beyond this level

- Of the ‘old’ biologics, ustekinumab has the highest persistence – anti-drug antibodies are less of a problem

- IL-17 blockers (e.g. secukinumab, ixekizumab and brodalumab) are effective after anti-TNF therapy has failed but less so when used first-line. In general, the more anti-TNFs failed, the poorer the response

- IL23-p19 inhibitors (e.g. risankizumab) appear to be highly effective with no new specific safety issues. In conclusion, Professor Warren said that early intervention with effective treatment achieved better outcomes.

Eczema can have a serious impact on quality of life for the child affected and the whole family. In addition, “there is a growing understanding that the chronic inflammation directly affects brain function, starting with mild symptoms such as separation anxiety and eventually progressing to depression, substance misuse and even suicide”, says Professor Mike Cork, consultant dermatologist, Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust.

Eczema can have a serious impact on quality of life for the child affected and the whole family. In addition, “there is a growing understanding that the chronic inflammation directly affects brain function, starting with mild symptoms such as separation anxiety and eventually progressing to depression, substance misuse and even suicide”, says Professor Mike Cork, consultant dermatologist, Sheffield Children’s NHS Foundation Trust.