Has obesity been normalised?

In Population Health

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

In an overweight society, obesity is normalised and sometimes even goes unrecognised. Community pharmacy teams are in a good place to help by engaging customers in a non-judgemental manner and if necessary signposting to further help

A bad diet is now killing more people globally than tobacco. Researchers estimate that, in the UK, poor diet cost 89,913 lives in 2017 compared with 96,000 deaths from smoking in 2016.1

Two-thirds of the UK population continue to be overweight or obese. Hospital admissions where obesity is a factor rose from 617,000 in 2016 to 711,000 in 2017 (two-thirds of which were women), while the Health Survey for England shows that between 2006 and 2016 the proportion of adults overweight or obese changed little.

In 2017, however, the survey returned the highest recorded level of obesity at 28.7 per cent. Childhood obesity is a particular concern. In the last year of primary school, on average, six children out of a class of 30 are obese and a further four are overweight, twice as many as 30 years ago. Obesity disproportionately affects children living in deprived areas.

The Government aims to halve childhood obesity by the year 2030 but is not on track to achieve this. Being overweight has become normalised across the population and parents often think that an overweight child is of healthy weight. This problem of perception creates a challenge in the fight against obesity.

A 2019 report by the Chief Medical Officer on solving childhood obesity2 says there are 1.2 million children in England with clinical obesity who require weight management services, with some requiring additional specialist services such as medication or surgical treatment. Many children are not getting the support they need to be a healthy weight as getting help often depends on where they live, not on their need.

The report says that too few health professionals are adequately trained and equipped to:

- Identify children and pregnant women who are overweight or obese

- Understand stigma and feel empowered to initiate conversations with children and families

- Support and manage overweight or obese infants and children, including those with associated ill health.

This problem of perception creates a challenge in the fight against obesity

The fight against obesity

The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh has called on the UK Government and the devolved administrations to provide universal nutritional education for parents to help tackle childhood obesity.

Of note is a scheme in Leeds where training for early-years workers and eight-week family programmes have been provided for 10 years. HENRY (Health, Exercise, Nutrition for the Really Young) is part of an obesity strategy delivered in children’s centres across the city.

Obesity rates at school reception stage have fallen from 10.3 to 8.7 per cent over a seven-year period. The gap between obesity rates at the age of five years in the least deprived and most deprived areas of Leeds is narrowing, with obesity rates dropping from 13.8 to 9.7 per cent in the most deprived areas over the past five years.3

Tale of the measuring tape...

- The National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) shows that in England one in 10 children are obese by the age of five years rising to one in five by the age of 11 years

- In Wales, 26.5 per cent of children aged four to five years are overweight and obese – higher than England’s 22.3 per cent for the same age group

- In Scotland, 10 per cent of children aged four to five years are at risk of obesity and 12 per cent of overweight – figures that have changed little in the last decade

- The 2017/18 Health Survey for Northern Ireland recorded a total of 8 per cent of children aged two to 10 years and 10 per cent of children aged 11 to 15 years as being obese.

Pharmacy weight management services

The NICE guideline on weight management services says, among other things, that a service for overweight or obese adults should be part of an integrated approach that involves pharmacy. NICE recommends multi-component weight management lifestyle services including programmes, clubs or groups designed to facilitate behaviour change to reduce energy intake and improve physical activity.

The aim is to reach a range of public health goals including reducing the risk of conditions associated with obesity such as coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, osteoarthritis, type 2 diabetes and various cancers (endometrial, breast, kidney and colon). A PSNC database has further information on pharmacy weight management services.4

A study in Aberdeen has found that community pharmacies can provide effective signposting to weight management services.5 Eight pharmacies successfully recruited 129 clients to the Scottish Slimming service and 97 attended at least one class, with 51 attending all 12 classes.

For the 97 who attended at least one class, after 12 weeks their mean weight loss was 3.7kg. One-third lost >5 per cent of their body weight and four clients lost >10 per cent. Many of the clients said they would not have addressed their weight if the pharmacy-based referral service had not been available. Pharmacy staff were positive about the service and said they would be willing to carry it on in the future.

Many of the clients said they would not have addressed their weight if a pharmacy-based referral service had not been available

Confusing advice

Dietary advice has become confusing as there is now so much information available from so many different sources that it can sometimes be hard to know which is most helpful and appropriate.

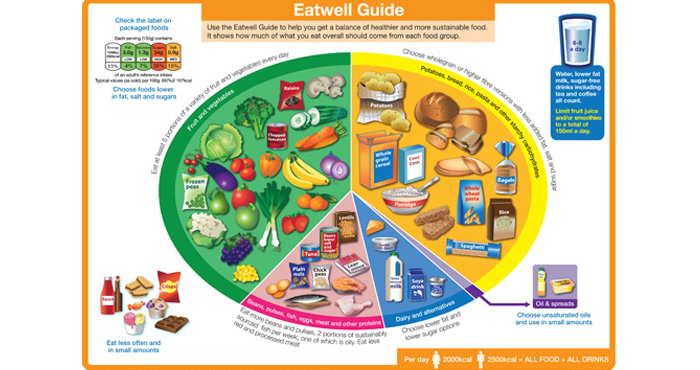

The focus of any general dietetic approach should be the NHS Eatwell guide6 (below) with an appropriately nuanced approach when working with individual clients and specific conditions.

Increasingly, national dietary guidelines, including Eatwell, have moved away from nutrient-based recommendations (e.g. consume x per cent of energy from carbohydrate or fat) to describe foods and dietary patterns. This accords with research supporting whole dietary pattern approaches rather than focusing on individual macronutrients (fat, carbohydrate, protein).

Neither a low carbohydrate nor a low fat diet is necessarily best for weight loss, says registered public health nutritionist Dr Emma Derbyshire. “A healthy diet is one that provides at least five portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables, meals that provide fibre, such as potatoes with their skins on and wholegrain cereal sources, some dairy or alternatives and a variety of protein sources including beans, pulses, mycoprotein, tofu/soya, fish, eggs and lean meat. It also needs to be portion controlled, rich in fibre, contain minimal alcohol and include water rather than calorific beverages. The best diets are those that can be maintained in the longer term and are not just a short-term quick fix.”

Dr Derbyshire thinks personalised approaches can be important. “We are all different physiologically and metabolically. If, for some people, cutting back on carbohydrate has worked and has benefits in terms of weight and blood lipid levels and enables them to be and feel healthier, then that is a positive result. From a generic stance, I would say that we do tend to under-consume fibre, which has important health benefits ranging from gut and digestive health to cardiovascular wellbeing. Cutting out carbohydrate can mean that we are cutting out fibre too – so this is worthy of consideration when looking at the bigger picture.

“In general, pharmacists can encourage diets that are balanced and varied. Any restrictive diets could have implications for micronutrient status. Vitamin D, iron and vitamin B12 shortfalls are some of the most common presently in the United Kingdom.”

Diet and diabetes

When it comes to managing people who have type 2 diabetes, Diabetes UK recommends an individualised approach to diet, taking into consideration the person’s personal and cultural preferences, and that people eat more of certain foods such as vegetables, fruits, wholegrains, fish, nuts and pulses with less red and processed meat, refined carbohydrates and sugar sweetened beverages.

The ideal proportion of macronutrients to recommend for optimal glycaemic control for type 2 diabetes is unclear, but total energy intake, weight loss and overall diet quality are significant factors. While carbohydrate content of the diet is a key determinant of glycaemia, evidence is limited with inconsistent findings, lack of studies of longer term effects, and lack of clarity on what constitutes the definition of low carbohydrate.

In a 2017 meta-analysis,7 low to moderate carbohydrate diets had a greater effect on glycaemic control (HbA1c) in type 2 diabetes compared with high carbohydrate diets in the first year. The greater the carbohydrate restriction, the greater the glucose lowering, but no differences in HbA1c were seen at 12 months. Apart from this lowering of HbA1c over the short-term, the meta-analysis showed no superiority of low carbohydrate diets in terms of glycaemic control, weight, or LDL cholesterol.

A recent two year-long study8 with good adherence found similar reductions in weight and HbA1c in both the low carbohydrate and high carbohydrate groups, but a greater reduction in diabetes medication was seen in the low carbohydrate group.

The exact proportion of energy that should be derived from total fat intake does not appear to be critical in people with diabetes. A study recommending up to 40 per cent of energy from fat (mostly unsaturated fat and a Mediterranean type diet) resulted in beneficial effects on lipid profiles, blood pressure and weight compared with a low fat diet9, while an intensive lifestyle intervention over four years, including a diet with less than 30 per cent fat (less than 10 per cent saturated fat), maintained significant weight loss and produced better overall levels of glycaemic control, blood pressure, HDL-C and triglycerides.10

These findings suggest that any effects of fat on CVD risk factors in type 2 diabetes are likely to be derived from the type of fat rather than the amount per se.

More intensive weight management can achieve remission of type 2 diabetes. One study showed partial or total remission in 11 per cent of people who achieved 8 per cent weight loss,11 and weight loss of greater than 10kg in 73 per cent of people with a surgically inserted gastric band.12 While sustained remissions have been reported after bariatric surgery,13 there remains a major challenge to maintain weight loss after non-surgical interventions.

The DiRECT study, funded by Diabetes UK, found that almost half (45.6 per cent) of recruited individuals with type 2 diabetes in 49 general practices in Scotland and Tyneside achieved remission (and were off diabetes drugs) on an intensive weight management programme.14

The intervention comprised withdrawal of antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs, total diet replacement (825-853kcal/day formula diet for three to five months), stepped food reintroduction (two to eight weeks) and structured support for long-term weight loss maintenance. At the end of year two, 36 per cent were still in remission. Remission was closely linked to weight loss with two-thirds of those who lost more than 10kg in remission after two years. The next step is to roll out the programme in a pilot scheme to 5,000 patients.

References

- The Lancet: Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017

- Time to Solve Childhood Obesity

- Health, exercise, nutrition for the really young (HENRY)

- PSNC

- Cambridge Core: A mixed-methods evaluation of a community pharmacy signposting service to a commercial weight-loss provider

- The Eatwell Guide

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2017; 5:e000354. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000354

- Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018 Apr; 20(4):858-871. doi: 10.1111/dom.13164. Epub 2017 Dec 20

- BMJ Open: A journey into a Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes: a systematic review with meta-analyses

- NCBI: Long Term Effects of a Lifestyle Intervention on Weight and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: Four Year Results of the Look AHEAD Trial

- NCBI: Association of an intensive lifestyle intervention with remission of type 2 diabetes

- NCBI: Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial

- NCBI: Diabetes and weight in comparative studies of bariatric surgery vs conventional medical therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- The Lancet: Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial