In Population Health

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

“Frankly underwhelming”, “an utter disappointment”, “embarrassing” and “inexcusable” are just some of the comments made by charities, experts and public bodies about the Government’s newly published childhood obesity action plan. Here we explore the proposals and the reactions

After a year-long delay, a promising report from the Health Select Committee in November 2015 and positive comments from health secretary Jeremy Hunt in which he referred to obesity as a “national emergency” and promised “a game-changing response”, expectations for the Government’s childhood obesity strategy were understandably high. Yet when it was published in August this year, the 13-page action plan was considered by many to be far off the mark in terms of its approach, focus and proposals.

The scale of the problem

Childhood obesity is regarded as one of the most serious global public health challenges of the 21st century by the World Health Organization (WHO). The 2014/15 National Child Measurement Programme for England revealed a third of 10- and 11-year-olds and over a fifth of four- and five-year-olds were overweight or obese.

Research suggests that overweight and obese children and adolescents are at increased risk of developing health problems such as type 2 diabetes, asthma, cardiovascular disease, mental health disorders and musculoskeletal problems, and are more likely to become obese adults. They will also have a higher risk of hospitalisation, morbidity, disability and premature mortality in adulthood.

But the impact of obesity on an individual is not confined to their health. They are also more likely to be unemployed, be absent from school or work due to sickness and experience stigmatisation, discrimination, bullying and low self-esteem. These factors can reduce productivity and put pressure and financial strain on health and social care services. In fact, more is spent in the UK each year on the treatment of obesity and diabetes than is spent on the police, fire service and judicial system combined.

It is thought that at the current rate, obesity in UK adults will reach 70 per cent by 2034, while over 35 per cent of boys and 20 per cent of girls aged six to 10 are expected to be obese by 2050. Consequently, over the next 20 years, NHS spending on obesity is expected to increase by a further £2 billion per year, up from the current £6.1 billion.

What was expected?

With statistics as alarming as these, it’s no wonder that there was so much pressure for a robust Government strategy to tackle the mounting obesity crisis. Among the solutions suggested by politicians, health experts, campaigners and charities, four were considered to have the most potential to help tackle the problem and were expected to be included:

- A sugar tax consisting of a minimum 10-20 per cent price increase on full sugar soft drinks, based on evidence that this measure has had a positive impact in other countries

- Reformulation of food and drink containing high levels of sugar and fat to make them healthier

- Stronger controls on factors that influence food choices, such as curbing the marketing and advertising of junk food, especially before the 9pm watershed, and banning price promotions on unhealthy food and drink in retail outlets

- A renewed focus on improving education and information about diet by raising awareness of concerns around sugar levels in the diet, encouraging action to reduce intake, and providing practical steps to help people lower their sugar intake.

What did we get?

The Government’s aim was to put into motion measures to “significantly reduce England’s rate of childhood obesity within the next 10 years”. The action plan states: “Long-term, sustainable change will only be achieved through the active engagement of schools, communities, families and individuals.” And it adds that the Government is “confident that our approach will reduce childhood obesity while respecting consumer choice, economic realities and, ultimately, our need to eat”.

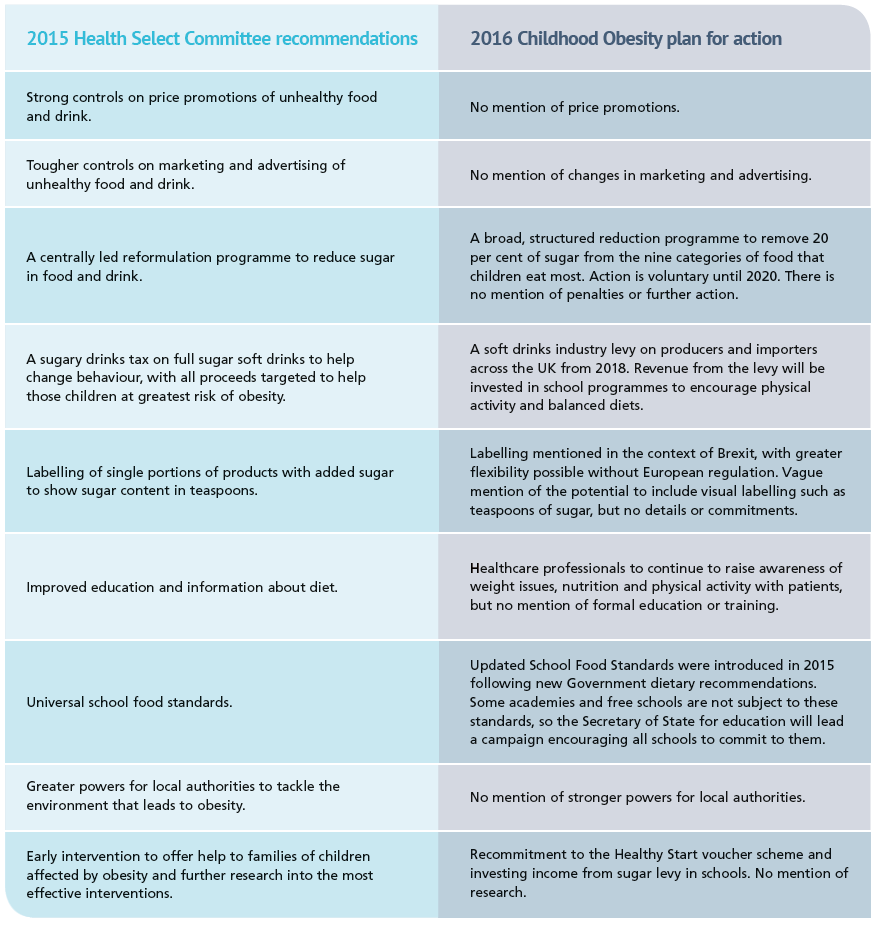

The table below compares the Health Select Committee’s 2015 recommendations with the actions outlined in the Government’s new plan, and it reveals significant discrepancies between what was expected and what was delivered.

Perhaps the most promising measure in the new plan is the confirmation that a levy on sugar will be introduced in 2018. Rather than a tax for consumers, this is a tax for manufacturers of sugary drinks that contain five grams of sugar or more per 100ml. The two-year time frame gives manufacturers the opportunity to reformulate their products to make them healthier and avoid the levy, thus tackling sugar consumption at a major source. The money raised from this tax will be invested in primary school sports and healthy eating programmes.

A two-month long consultation on the levy began on 18 August to allow industry and health experts to consult on a range of technical details, such as if some drinks should be excluded, and how to protect the smallest producers.

The response

The sugar levy and the soft drinks industry’s reformulation plans have largely been welcomed as positive steps towards reducing the nation’s sugar consumption. Chris Askew, chief executive at Diabetes UK, says that the charity looks forward to working with the Government through the consultation “to explore ways of introducing the levy so that it is effective and does not negatively impact on people living with type 1 and type 2 diabetes and their families who rely on high-sugar products to treat low blood glucose levels”.

In the same vein, Judy More, paediatric dietitian and Infant and Toddler Forum (ITF) member, says the ITF: “Welcomes any development that supports parents to better manage sugar consumption in their young children’s diets, makes them aware of the importance of doing so, and helps them put this into action.”

The focus on schools making children healthier and more active has also been applauded, with Shirley Cramer CBE, chief executive of the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH), saying: “It is of course welcome to see further investment in school sport and that Ofsted inspections will now take into account how schools support their pupils’ health.”

However, the general consensus seems to be that in isolation, these measures are not sufficient to have any meaningful impact on the obesity crisis, and other actions that would have ensured more comprehensive change have been ignored or watered down.

The most wide-spread criticism has concerned the omission of controls on junk food marketing, advertising and promotions. “[It feels] like several pages of the plan are missing; there is a glaring omission around any measures to tackle the aggressive marketing of junk food – on TV, online, and through sponsorship and price promotions,” says Shirley. “Such marketing and promotion was identified as a critical area for action by Public Health England in its sugar reduction report last year. It is therefore extremely disappointing that these evidence-based recommendations have been dismissed.”

Anna Feuchtwang, chief executive of the National Children’s Bureau (NCB) agreed, saying: “The Government’s failure to stop the aggressive marketing tactics used by the food and drink industry could undermine efforts to reduce childhood obesity.”

The fact that the actions in the plan are not mandatory has also been criticised, with many people under the impression that voluntary targets will mean that progress will be slow and somewhat limited. Professor Parveen Kumar, chair of the British Medical Association’s Board of Science, goes so far as to say that “although the Government proposes targets for food companies to reduce the level of sugar in their products, the fact that these are voluntary and not backed up by regulation, renders them pointless”.

Chris Askew agrees that regulation is key to success and also suggests that reducing sugar intake shouldn’t be the sole focus as other factors contribute to obesity. He says: “The measures we urgently need to see implemented include setting ambitious targets, backed by regulation, for food manufacturers to reduce the saturated fat, salt and added sugar content of their products.”

However, there has been no word from the Government about extending the measures to other hidden nasties such as saturated fat and salt, and it has ruled out expanding the levy on sugar to include other foods, instead the Department of Health has said: “The Government hopes this levy will encourage the entire food and drinks industry to play their part in developing products with lower sugar content.”

The NCB has criticised the plan, arguing that there is not enough focus on utilising local health professionals. Anna Feuchtwang says that while a sugar tax and reducing sugar content will help more children eat healthily, money raised through the sugar levy “must be used to shore up recent cuts in public health spending so we can encourage more children to understand how the food they eat affects their health.”

For details on the plan and the affected food groups, see: the Government's plan here.

The role of pharmacy

The key to tackling the obesity crisis is prevention, and this is where pharmacy has great potential to help. Leyla Hannbeck, chief pharmacist at the National Pharmacy Association (NPA), explains more

There are two ways to help curb the rising obesity crisis:

- Promote lifestyle changes, including dietary and physical activity advice

- Target patients who are obese but who do not see their GP regularly as they have not developed any associated health conditions. Community pharmacies are well placed within local communities to help raise awareness of the dangers of obesity. Pharmacy staff see patients regularly and are therefore able to speak in confidence with them about such issues, as well as being able to offer weight loss services, and obesity-related services such as blood glucose testing.

Pharmacy staff have great skills in identifying and managing patients who are overweight and obese and offering them regular and non-discriminatory advice. It is paramount that pharmacy staff use their clinical judgement rather than stereotyping to ascertain whether a customer is overweight or obese. All staff involved should be trained to start conversations, and standard operating procedures and accurate records should be put in place.

Choosing a quieter time to start conversations is important in order to minimise the risk of being overheard. However, any further conversation should be offered in a consultation room to help the customer feel at ease.

Obesity is a condition that can be prevented and treated with behavioural therapy and lifestyle changes – only when dietary and physical activity interventions have not helped would a patient be referred for drug treatment.

Pharmacy staff should also be aware that losing weight is not about looking a certain way or being a particular dress size. Staying within a healthy body mass index (BMI) is important and can decrease the risk of associated health conditions which may include cancer, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, respiratory problems and type 2 diabetes.

Finding out what is happening locally and promoting these activities is also a great way of speaking to customers. This includes local healthy eating or physical activity clubs and even exercise in the park.

There is a glaring omission around any measures to tackle the aggressive marketing of junk food